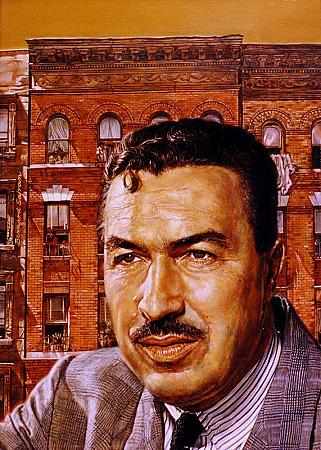

During the middle girth of this century, Adam Clayton Powell Jr. was the equivalent of the rap group Public Enemy, the protest politician Jesse Jackson, and the Congressional Black Caucus all in one.

During the middle girth of this century, Adam Clayton Powell Jr. was the equivalent of the rap group Public Enemy, the protest politician Jesse Jackson, and the Congressional Black Caucus all in one.

Like Public Enemy, Powell “dissed” white America for its racism and hypocrisy, with one of his clearest refrains being akin to “You Can’t Trust ‘Em.” When he demanded changes in society, Powell, as Jackson would years later, commanded so much attention in Washington and with the media that he became known as “Mr. Civil Rights.” And as the first African-American congressman from the northeast, and for decades the only militant African American on the Hill, Powell had the guts to push through laws that forced America to stop locking African Americans out of industries and institutions.

He didn’t behave like most African-American politicians. “I’m the first bad Negro they’ve had in Congress,” he bragged. He made more enemies on Capitol Hill than perhaps any legislator before or since.

He didn’t behave like a typical African-American minister. “I believe only in the teaching of Jesus,” he said, “I am not a full-Bible Christian.” And he felt this distinction gave him wide moral latitude. He openly drank alcohol, smoked, and had adulterous affairs. When he strode up the aisle of his packed church to preach, women parishioners later admitted to being distracted from thoughts of God by enrapture with the tall playboy- minister.

Powell was born in New Haven, Connecticut, in 1908. His father, who missed by one month being born into slavery, pastored the most prestigious African-American church in New York City, Abyssinian Baptist.

He stopped and started through a checkered college career, first attending City College of New York. Eventually, he flunked out. After that, Adam went into a serious party mode. These were the Roaring ’20s. Harlem, with hundreds of speakeasies, rent parties, and dance halls, was a wild bachelor’s paradise. The little money he made as a kitchen helper, he spent on gambling, women, and liquor.

But Adam’s father pushed him back into college, this time to almost all-white Colgate University in up-state New York. Young Powell began studies to become a surgeon but, later, with some prodding, realized that one day his father’s well-off church could be his for the asking, so he changed his mind about medicine to become a healer of souls.

Upon graduation, his parents gave him a present of a trip to Europe, the Holy Land, and Egypt. When he returned, he enrolled in Union Theological Seminary, then later in Columbia University Teachers’ College, where he eventually took a master’s degree in religious education.

While he worked on postgraduate studies, Powell helped thousands in his community to eat and find clothes and jobs. The Great Depression had America on the dole and in despair. As assistant pastor under his father at Abyssinian, Powell helped operate a free food pantry, job referral service, and literacy classes. His compassion became legendary when it was rumored that Adam once took the shoes from his own feet and gave them to a poor man for whom the church clothing bin had no proper sizes.

As he matured into adulthood, Powell began speaking out against the institutional racism ingrained in New York. In a short time, he racked up successes in getting jobs back for doctors, forcing bus companies to hire African-American drivers and mechanics, as well as squeezing white store owners with the “Don’t Buy Where You Can’t Work” campaign.

“It’s in your hand,” he admonished his people. “Just like little David had those smooth stones and killed big Goliath with them. Use what you have right in your hand. That dollar…that ten cents. Use your vote. The Negro race has enough power right in our hands to accomplish anything we want to.”

In 1941, he became New York City’s first African-American councilman. By 1944, he had won a seat in Congress. It was heady, but lonely as one of the only two African Americans in the U.S. House; particularly since the other, William Dawson of Chicago, was more seen than heard, careful to not upset the status quo.

Adam immediately ripped into Congress for allowing lynching of African-American men to continue. He railed against the unconstitutional Southern practice of charging would-be, African-American voters “poll taxes.” Even Democratic presidents Roosevelt and Truman, who owed African Americans for having voted for them, had to be dragged into issuing executive orders ending discrimination in military bases and war factories. If his colleagues ignored him and voted down his proposals; if Truman, or Eisenhower, Kennedy, or Johnson wouldn’t grant him a personal session to discuss civil rights or helping the poor, Powell made vicious public statements or sent embarrassing “open” telegrams to the press describing their insensitivity.

Powell perfected a role as agitator. “Whenever a person keeps prodding, keeps them squirming…it serves a purpose. It may not in contemporary history look so good, but…future historians will say, ‘They served a purpose.”‘

He was African-American pride personified. He swaggered into the congressional dining room and barber shop Knowing full well that African Americans were not served there, and demanded service. He won it. He badgered racist congressmen and stopped their habit of saying the word “nigger” in sessions of Congress.

One of his most dangerous legislative weapons was the “Powell Amendment,” a rider he tried to attach to any proposals for federal funds. The beauty of the Amendment was that, if successfully attached to a bill, it would nullify federal grants to state or local governments if the agencies receiving the money discriminated. This meant, for example, that even school districts in the deepest South had to open their doors to African-American teachers and students or I risk losing funds set aside for them.

Voters from Harlem elected Powell as their representative nearly two dozen times. With long service in Congress comes seniority and ultimately the chance to head one of the powerful committees that draft bills that the full House and Senate eventually vote on. After the election of 1960, Powell took over as chairman of the House Education and Labor Committee. In that role, he had more concrete power than any African- American man on the planet. His little club, as it were, could initiate proposals worth billions of dollars and decisions affecting millions of Americans, and hundreds of schools, labor unions, and employment practices.

Here was where Powell made his greatest contributions. He oversaw passage of the backbone of President Kennedy’s “New Frontier” and President Johnson’s “Great Society” social programs: A sweeping anti- poverty bill, an increased minimum wage, a National Defense Education Act that benefitted generations of high school and college students.

Yet in the new book, Adam Clayton Powell Jr.: The Political Biography of an American Dilemma, Columbia University professor Charles V. Hamilton, an African American, courageously addresses old allegations that Powell misused his clout to clean up consequences of his personal excesses.

The extravagant New Yorker suffered more than a decade of court cases over tax fraud, and for taking kickbacks from employees who no longer worked for him. Hamilton presents evidence that Powell supported Republican president Dwight Eisenhower for re-election in 1956 in exchange for a promise that Ike would kill the investigation.

There is no denying, however, that despite his commitment to civil rights for his people, Adam Powell Jr. was no paragon of virtue. He was egocentric, self-indulgent, and often treacherous. To keep Martin Luther King Jr. From picketing at the Republican convention where Eisenhower was to be nominated, Powell threatened to publicly (and surely, falsely) announce that King was having a homosexual relationship with another civil rights activist, Bayard Rustin.

He had no permanent friends, only permanent interests. At some points, he aligned with traditional civil rights groups, then when it suited his purposes he’d accuse them of being made up of Uncle Toms not worthy of African Americans’ support.

Ultimately, Powell used up his political currency. Members of the House, happy to find a reason to silence him, expelled him for pocketing congressional employment paychecks to his wife, and for taking junkets abroad with female staffers. The fighter in him took the case all the way to the Supreme Court. He won back his seat. Even then, he was docked $25,000 to repay the illegal kickback. But the people of Harlem grew tired of Powell’s unbelievable record of roll call absences and endless litigations. In 1970, they finally voted him out. Two years later, he died of prostate cancer at the age of 63.

Today, he isn’t as ubiquitous a symbol of African-American determination as Malcolm X; you seldom find his likeness on t-shirts, or see film clips of his speeches within music videos. Nor is his picture reverently displayed in magazine ads during Black History Month like Martin Luther King, Jr.’s. But African Americans with a knowledge of their history remember Powell as the risk taker who made it possible for later generations of African-American politicians such as Jesse Jackson, Rep. Ron Dellums, and Willie Brown of the California Assembly to stand unbowed in the arena of political horse trading.

And in Harlem, where a state office building and a broad boulevard are named for him, you can occasionally still visit an apartment home where his picture adorns a place of honor.

http://www.black-collegian.com/african/adam.shtml